Politics.

I saw you cringe. It’s one of those topics not fit for polite conversation. It may be entertaining for some, intensely interesting for others, but for many it’s one of those “change the subject” kind of subjects.

But politics are everywhere. There are politics any time we humans organize ourselves in order to make decisions for our collective interest. Actually, that’s pretty much the definition of “politics.”

But politics are everywhere. There are politics any time we humans organize ourselves in order to make decisions for our collective interest. Actually, that’s pretty much the definition of “politics.”

And any time we are talking about making decisions, we’re talking about power: the ability to bring about change. Where there’s politics, there’s power.

Yep, there are even politics and power dynamics in church. Yep, even your church.

Politics and power are inevitable in collective human life. They are neither good nor bad; they just are.

But I sure do understand that feeling of “Ugh!” when you hear the word “politics.” After all, so much of the way we do politics—you might say “the politics of the world”—is just not very nice.

We polish up our résumés and show off our good sides: all strength, no weakness allowed.

We shore up support through strategic relationships and backroom deals and hollow promises.

We appeal to our base through polarizing rhetoric: it’s “us” versus “them.”

We listen to those who agree with us, and we ignore—or even disdain—those who don’t.

We appeal to truth—when it’s convenient for us. Otherwise it’s half-truths, sometimes a full-on lie.

We manipulate emotions through sugary, empty rhetoric. Our only harsh words are for our opponents.

We take control whenever we can, holding all the crucial resources and making all the important decisions.

We do all this either consciously (“That’s just politics!”) or subconsciously (our capacity for self-deceit is astonishing).

And we do all this, we like to think, for the ultimate good of all. We know what is best, and we’ll do whatever it takes to bring about that ultimate good. In the politics of the world, the ends justify the means.

I bet you think I’ve just described politics in Canada or America. That may be, but what I actually had in mind was politics in the church.

Go back through the list again. That, all too often, is church politics. That, folks, is just politics, whether in the church or in society.

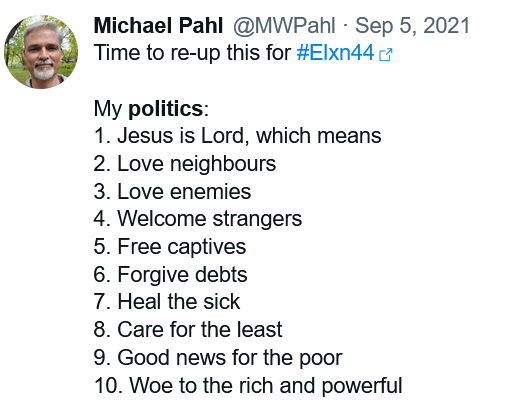

But Jesus calls us to another way. Jesus calls us to a radically different politics, a radically different power.

The gospel—and the Gospels—are shot through with Jesus’ upside-down politics and power.

Jesus is anointed by God’s Spirit and appointed by God’s decree: “You are my beloved Son (my chosen Messianic King, in other words); with you I am well-pleased (my chosen Suffering Servant, that is).” Jesus is King, but he’s not like other kings. Jesus brings in a kingdom, but not the way other kingdoms come.

Jesus then immediately and persistently follows through on this: he resists the temptation to seize power through evil or idolatrous means, to establish God’s kingdom through the use of overwhelming force or meticulous control—in stark contrast to the ways and means of the world.

Instead Jesus teaches love of God, love of neighbour, even love of despised enemies—and then he goes out and does it: embracing those on the fringe, exhorting those at the centre, attending to the weak, admonishing the powerful.

Since his followers are slow to get the point, he states it bluntly: “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. It will not be so among you; but whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave; just as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.”

Since his followers are slow to get the point, he states it bluntly: “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. It will not be so among you; but whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave; just as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.”

And finally, in the penultimate end, Jesus is enthroned on a cross. He gives his life for the good of others, he embraces utter weakness and relinquishes total control, he refuses right to the bitter end to respond with raw power or naked force. In the politics of Jesus, the means—the ways of the cross—are the ends.

In the middle of all this is a familiar story that sums up Jesus’ approach to politics and power.

In the story Peter declares that Jesus is indeed the Messianic King. Jesus accepts his declaration, but immediately emphasizes that the way to his throne is the way of the cross. Peter then rebukes Jesus: That’s not the way kingdoms are won! That’s not how the world changes! Everyone knows this, Jesus!

And in turn, Jesus rebukes Peter, with words that should strike holy fear in the heart of anyone who claims to be a Christian: “Get behind me, Satan! For you are not thinking the way God thinks about such things, but the way the world thinks.”

You are not thinking the way God thinks about such things—about kings and kingdoms, about politics and power—but the way the world thinks.

The world’s politics are about “strong power.” Overwhelming physical presence. Personal charisma and authority. Psychological intimidation and emotional manipulation. Coercive words, polarizing rhetoric, and subtle deceit. Full control.

Jesus’ politics are about “weak power.” Humility, not pride. Compassion, not apathy or antipathy. Persuasion, not coercion. Forgiveness, not blame. Persevering faith, not fear. Self-giving love, not self-serving self-interest.

The world’s politics are tempting, to be sure. You can get quicker results when you force your way through, when you unilaterally push your agenda for a better world. And the longer you spin your wheels trying to achieve a goal without results, or the more pressure there is to bring about a certain objective, not now, but right now—the more tempting it is to resort to strong power.

But the history of humanity—and the smaller stories in our own lives—show over and over again that these “good” results through strong power simply do not last, and they’re often more damaging in the long run. Even in the short run, there are almost always innocent victims, physical or psychological or emotional casualties left in our wake.

Jesus’ politics take longer to achieve any good thing—like small seeds growing, or yeast working through dough—and they demand much more of us—our very lives, in fact. But the end result is shalom for all involved: wholeness, harmony, justice, and abundant life.

So what does all this have to do with church politics? What (gulp) might this even have to do with politics of any kind?

Everything, in every way.

We must resist the temptation to bring about change, even positive change, through strong power. Strong-arm tactics, passive-aggressive behaviour, divisive fearmongering, meticulous control, and more, have no place—no place at all—among followers of the crucified Jesus, whether in the church or beyond it. We need to have a patient, persevering faith, truly trusting that God’s way, the way of weak power, is in fact best.

We must repent of the ways we have engaged in strong-power politics. Again, our capacity for self-deception and self-justification is truly astonishing. This is especially so when we are convinced that our way is the best way, or that we hold the morally superior or theologically correct position. We need constant, rigorous self-monitoring and self-examination—and the humility to accept correction by others.

We must embrace Jesus’ way of weak-power politics. Seeking to persuade rather than coerce: speaking truth to power, showing compassion for weakness. Serving others in humility, not posturing before others to gain status or controlling others to ensure the change we want to see. Forgiving others when they fail, not pouncing on their faults for political leverage. Patiently pursuing long-term shalom rather than short-term gain.

We must embrace Jesus’ way of weak-power politics. Seeking to persuade rather than coerce: speaking truth to power, showing compassion for weakness. Serving others in humility, not posturing before others to gain status or controlling others to ensure the change we want to see. Forgiving others when they fail, not pouncing on their faults for political leverage. Patiently pursuing long-term shalom rather than short-term gain.

In particular, we must always attend to those on the margins. Always. Even when the margins shift, and those on the outside become those at the centre, and others are now on the margins. And especially when we’re the ones at the centre—along with our friends and family and all our favourite people. Any power for change we possess—through position, wealth, education, whatever—must be used in the way of the cross for those without such power, especially the most vulnerable and unjustly treated.

In other words, we must set aside our cultural brand of Christianity with its ways of the world and respond to Jesus’ radical call to discipleship: “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.”

This is politics and power, the Jesus way. And it’s the only way to find real life: for you, for the other, for all.

Cross-posted from http://www.mordenmennonitechurch.wordpress.com. © Michael W. Pahl.

But politics according to Jesus does intersect with the politics of the world. When Jesus proclaimed the “kingdom of God,” he was claiming an alternative vision to the kingdoms of the world. When he brought “good news to the poor,” he was declaring a very different “good news” than that claimed by the Roman Empire. And all that Jesus-y stuff I listed in the previous paragraph? That’s the stuff that our politics—the ordering of society, collectively making decisions—is concerned with.

But politics according to Jesus does intersect with the politics of the world. When Jesus proclaimed the “kingdom of God,” he was claiming an alternative vision to the kingdoms of the world. When he brought “good news to the poor,” he was declaring a very different “good news” than that claimed by the Roman Empire. And all that Jesus-y stuff I listed in the previous paragraph? That’s the stuff that our politics—the ordering of society, collectively making decisions—is concerned with.

Walter Wink

Walter Wink

Nobody said U.S. politics were dull.

Nobody said U.S. politics were dull.